| Language Matters Home | Language Matters I | Language Matters II | Language Matters III | Language Matters IV |

| Discussion Board | Resources | Novel Discussions | |||||||||

| The Bluest Eye | Sula | Song of Solomon | Tar Baby | Beloved | Jazz | Paradise | Love | A Mercy | |||

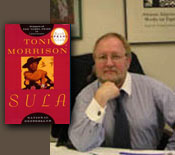

Sula

Keith Byerman is a professor of English at Indiana State University and author of many books on African American fiction, including Fingering the Jagged Grain. A frequent presenter at seminars and institutions for high school and college teachers, he is a leading scholar on contemporary African American literature, especially Toni Morrison and John Edgar Wideman.

Keith Byerman is a professor of English at Indiana State University and author of many books on African American fiction, including Fingering the Jagged Grain. A frequent presenter at seminars and institutions for high school and college teachers, he is a leading scholar on contemporary African American literature, especially Toni Morrison and John Edgar Wideman.

Novel Discussion

Dr. Keith Byerman: I want to start with a story related to a question that I want to pose, because I've never quite resolved it. Then we'll deal with a couple of other questions and some of the issues related to Sula.

I remember when I was teaching at the University of Texas twenty years ago, I had a young African American woman who was interested in creative writing. She wanted to do an independent study course with me on African American women writers. She was looking for more levels for the kind of work she was interested in doing. This was a nontraditional student. She had a child. She'd been married and divorced. We were reading a couple of Morrison novels. She was interested as much in questions of craft and audience as she was in the traditional kinds of stuff that we'll be looking at.

We started the conversation by talking about which Morrison novel we liked the most. This was pre-Beloved. We had a smaller range of opportunities. I said that I loved Sula. At that point that was my favorite Morrison novel, and in some ways it still is. She said, "That's not surprising." She said, "Sula is a novel that men like." I wonder how you respond to that. I found it intriguing, given that it's a book about the friendship of women, given that it's a book in which we have characters named Boy Boy, Tar Baby, and Chicken Little, and they act out their names in a lot of ways.

Are there reasons why this novel would appeal to men? She obviously was a person who had read a lot of Morrison. She didn't pick Song of Solomon as the one that men would like. She picked this one. Why was that? This is a hypothetical question.

Participant: Maybe because Sula’s betrayal of her friends and the sexual encounter with her husband may support the men's perspective that women will do anything to get a man and let their friends fall by the wayside.

Participant: My friend said he liked it because Sula and Hannah had a love-him-and-leave-him attitude, and they didn't show attachment.

Dr. Keith Byerman: Part of what my student said was that it's not only the novel but also the character Sula that men would like.

Participant: She enjoyed her conversations with Ajax and that free love.

Dr. Keith Byerman: I think there is something about the character of Sula that in some curious way represents certain values and a certain consciousness that we traditionally and conventionally associate with men, as opposed to Nel, for example.

Think about the character of Sula. She is independent. She goes off on her own. She doesn't seem to care what other people think about her. She can just walk away. She is willing to confront people—the whole business with cutting off the tip of her finger in an encounter with a group of boys. An important idea that comes out of this is that one of the ways in which Morrison—remember this is an early novel for Morrison (1973)—with a character like Sula is already challenging our notions of what gender involves. She's already challenging what we might call gender essentialism, that women have to be a certain kind of way and men have to be a certain kind of way. We'll get into more about what happens with Sula and what Morrison might be saying about that kind of woman, if there is such a thing as "that kind of woman," because that might get us into another version of gender essentialism, when we look at the character of Sula and Sula's destiny.

One of the things we don't often talk about with Morrison is what amounts to her poetry. Here is the opening paragraph of Sula:

In that place, where they tore the night shade and blackberry patches from those roots to make room for the Medallion City Golf Course, there was once a neighborhood. It stood in the hills above the valley town of Medallion and spread all the way to the river. It is called the suburbs now, but when black people lived there it was called the Bottom. One road, shaded by beeches, oaks, maples, and chestnuts, connected it to the valley. The beeches are gone now and so are the pear trees where children sat and yelled down through the blossoms to passersby. Generous funds have been allotted to level the stripped and faded buildings that clutter the road from Medallion up to the golf course. They're going to raze the Time and a Half Pool Hall, where feet in long tan shoes once pointed down from chair rungs. A steel ball will knock to dust Irene's Palace of Cosmetology, where women used to lean their heads back on sink trays and doze while Irene lathered Nu Nile into their hair. Men in khaki work clothes will pry loose the slats of Reba's Grill, where the owner cooked in her hat because she couldn't remember the ingredients without it. (3)

That's amazing writing. It catches the specifics of a place. It's a process of naming. The shack called Irene's Palace of Cosmetology. What a wonderful name. It's that sense of language. We often talk about other ways in which Morrison uses the language, the way in which she will give us these unclear references or she will set something up at the beginning and then we'll come back to it. Sometimes she just does this. It gives you the sense of a place, a community, and a culture in relatively few words. There's a touch of humor to it. There's a sense of history to it. It's in some ways remarkable.

Later in the course, when we discuss Paradise, I will ask you to consider who the hero of that novel is. Similarly, what I will ask you to consider for Sula is, Who’s story is this? There are lots of answers. It's a key question because it helps us to decide where to focus our attention. Different audiences will have a different sense. I think to the extent that my student was right that this is a story that men like is based on seeing Sula as the central character. It's also easy to suggest that this is Nel's story or that it's the story of a community and not the story of an individual character. We'll get back to that.

One of the suggestions about the primal nature of what's going on in this book is that it clearly offers us a set of symbols that are the most fundamental symbols that we have in literature: earth, air, fire, and water. They all play key roles in this text. For those who would like to read Sula as a lesbian novel, as people have suggested, we have that wonderful scene of Sula and Nel together digging the hole [earth]. We have all the fires—Plum, Hannah. We have the water of Chicken Little’s drowning and the water of that attempt to put out Hannah. We have the air of Eva upstairs, floating above the rest of the world in some sense. All of these elements are put into play in a variety of ways in an interesting culmination.

Sula’s Structure

It's a story that on the surface at least is very easily structured. The chapter titles are years, essentially, the years between the first and second world wars. They're designated. Something happens in each of those chapters that is associated with that date. We have none of this mess of Paradise where you're trying to figure out when something happens—even when she tells you what year it is, you're not sure if she really means it. Here you know she means it. We do have those Morrison tricks. We have a novel titled Sula in which the character of Sula doesn't appear for about forty pages. We tell a bunch of other stories and eventually we get around to the title character. It's not clear that the stories in the early chapters are in any obvious way connected to the character of Sula. We have the story of Shadrack. We have the story of Helen or Helene, depending on whom you talk to. Nel is connected to Sula, but the story that is told before we get to the character Sula is not in any way directly related to the character Sula herself. There is the story of Plum and the story of the Deweys, which is the best story of all, I think. We're talking about “identical” triplets who are not the same ages, who don't look alike, and quite possibly are not the same race, but nobody can tell them apart. What are we supposed to do with that?

This is a novel that's about the relationship between the community and the individual. Paradise works by a process of exclusion and careful inclusion, but what happens in Sula is that almost anybody can be included. That's one of the functions of these early chapters.

Extreme Characters

This is one of the novels in which Morrison creates extreme characters. In Paradise Morrison creates extreme situations, but she doesn't necessarily create extreme characters. Here we have extreme characters: a man who has gone through the first world war, is afraid of his own hands, doesn't quite know what to do with the face he sees in the toilet, and creates National Suicide Day. There is also a woman who apparently has her own leg cut off in order to save her children and then sets herself up as a kind of queen. She then sets her own son on fire. Her daughter will have sexual intercourse with any man but won't sleep with them because sleeping implies trust. She gets a little loving every day in the pantry—and nobody minds. Then she ends up getting set on fire and scalded to death on top of the fire.

The Deweys play games like chain gang. They don’t have any other names. We have a white man named Tar Baby. These extreme characters are beyond the pale in terms of normality. This seems to be an early Morrison pattern. If you think about the characters in Bluest Eye, there is a similar situation of extreme characters. What happens in this book is that each of those characters manages to be integrated into the community in some way. When Shadrack comes back from the war and lives in his hut on the edge of town and every once in a while goes out on a rant and screams obscenities at people and exposes himself, people sort of understand. When he creates National Suicide Day so that dying won't be disorderly and we can get it all done at once and be done with it for the year, people start saying, "Let’s get married in January but not on National Suicide Day." It simply becomes a part of the life of the community.

Eva becomes a part of the life of the community with her utterly bizarre house that has some rooms that are all doors and some rooms that have no doors. Some rooms you can't get to from any of the other rooms. She sits up on the third floor and all the men come to her like a queen. Hannah is part of the community. Eventually the women come to have no problem with Hannah’s sexual behavior, because they see it as a sign of respect. She respects their men. Helene thinks she is black Creole but probably isn't. She's from New Orleans. Everyone turns her into Helen as a way of integrating her into the community. Everybody belongs. Everybody can be accommodated in some ways without sacrificing their eccentricities and their actual character. You just work around them. You work with them. It's a place where community can incorporate individuals without much difficulty.

The white man, Tar Baby, lives there in the house. He's quietly alcoholic.& He doesn't bother anybody. In Paradise we have challenging of notions of community, while in Sula we have a positive notion of community—at least in a conventional sense. We'll have to work through that idea. This goes back to my question.

The Relationship between Community and the Individual

This novel is about the relationship between community and the individual in part. The relationship between Sula and Nel is the story that people probably like best in this book. These very different young women are fast friends. Sula loves the order of Helene's house, and Nel loves the vitality of Eva's house. They get what they need from each other. They are not friends because they are alike. They are friends because they're complementary. They give each other a shape.

What isn't talked about enough is Sula's relationship with Ajax. Before everything else, they are friends. They are people who understand each other. One of the things that is often ignored with Ajax is that his relationship to his mother determined the kind of man that he is. She was a powerful figure in his life. From his mother he learns the value of freedom and identity. There are two things we could do with what happens to that relationship between Sula and Ajax. One is by looking at Ajax and saying when Sula starts creating this nest for him he wants to get away from it. He couldn't deal with it. It's too confining. It's too restrictive. The other way to read that, however, is to suggest that what Sula has done is to fall into the trap of conventional gender roles. That what Sula thinks she wants at that moment is something that is perfectly stable, something that is ordinary. Something like what Nel has.

I would argue that the problem is not Ajax; rather, it is Sula. Sula is giving up her own sense of self. Remember what Jude’s vision of marriage is? On his wedding day, he thinks of Nel, his new bride: "The two of them together could make one Jude." (83). Sula's mistake is that at some level what she wants is to make one Ajax. Ajax doesn't need it and neither does Sula. It's the model that's there. She compromises her sense of self in order to move toward that. He says, "No." One of the things that marks that for us is when she sees his driver's license after he's gone. She's misnamed him all along. She thought he was Ajax when he was A. Jacks. In other words, she was turning him into a mythological creature, the all-powerful male. That's not what he was. He was A. Jacks.

The friendship between Ajax and Sula leads us to talk about the relationship between freedom and responsibility. It's a classic set of oppositions. One way to read the book is that Sula equals freedom; Nel equals responsibility. Nel had grown up with a clothespin on her nose so that it would get narrow—I've talked to people from New Orleans who'd actually had that experience themselves.

Participant: My mother had that done. Her father used to do that.

Dr. Keith Byerman: This is not made up. It's another aspect of colorism [the belief that the lighter one's complexion, the more beautiful, and/or intelligent, and/or sophisticated one is; a form of internalized racism in African diasporic communities]. Nel is the one who gets married. Nel is the one who rejects Sula, because Sula has an affair with her husband. We need to clarify some things about that relationship too.

The Costs of Freedom and Responsibility

Morrison talks not only about the virtue of responsibility but also about the cost. If you sacrifice yourself to make one Jude, what happens when there is no Jude? You get those empty thighs that she writes so wonderfully about. It's another one of those great poetic passages. It's not quite a blues song but very close.

On the other hand, what about freedom? Choosing to cut off the tip of your finger. Choosing to walk away when Nel gets married and be gone for years. Choosing to come back and sleep with all of the men, some of whom probably slept with your mother—didn't sleep with, had sex with. Your relationship with them is considered an insult, but you don't care. Sula is the one with the more interesting life. Sula is the one who has experienced the larger world. Sula knows things that Nel can never know. But Sula is alone.

One of the things that freedom can cost you is community. If you're going to insist on your independence, you lose your place in the community quite often. Sula in some ways is typical of all those students who go off to college and then come home and nobody quite knows what to do with them. They don't quite fit anymore. They don't fit with their families. They don't fit with their friends. They just don't quite fit. Multiply that to the nth degree and you've got Sula. When she gets sick, who's going to take care of her? This woman puts her own grandmother in a nursing home, not because Eva needed to be in a nursing home because she was ill or because she was incapacitated, but because Sula was afraid of her. Freedom is costly, as is responsibility.

Achieving Personal Identity

If you associate personal identity with freedom, with individual choices, then the question becomes by what do you measure your success or failure at achieving identity? Morrison has said that Sula was an artist without a form. What she wanted to make was herself. How do you go about doing that, independent of context, independent of community, especially when you have a grandmother like Eva and a mother like Hannah? It complicates the notions of womanhood for you. If your mother is Helene, you know how to establish your identity. You take off the clothespin. In some ways, that's simple. It's something Nel never actually does, but it's relatively simple. If you live in Eva's house, what do you measure yourself against? What do you use as the friction by which you shape yourself and the things that carve out your face? Personal identity is crucial in this book.

That has to do also then with mothers and children. This is very much a book about mothers and children. Sometimes it's about orphans—usually it's about orphans—but mothers are very prominent in this book. Helene trying to reconstruct Nel in her own image. Even her naming suggests that. She's going to be Little Helen. Eva—we can play with her name, of course. Eva, like the Biblical Eve, is the mother of everyone. Little nameless boys, white alcoholics, a drug-addicted son, a sex-addicted daughter, apparently a promiscuous granddaughter, and the brides and grooms who come to live in her house for a while on their way to their own lives. She's everyone's mother. Would you want her for a mother?

Eva is the woman who says that she has to kill Plum, because what he is trying to do is return to her womb. She feels she has a right to destroy him, because, after all, she brought him into the world and saved his life. Now he has rejected that life. She takes him out of the world. Then, in what might be interpreted as a kind of justice, Eva has to sit and watch as Hannah burns up. Because she doesn't have her leg, which she sacrificed for her children, she cannot save her daughter. Play around with the ironies in that.

If mothers and children are one story, the lives of men are another story that's offered to us. Shadrack, the man who sees the face of his fellow soldier blown off as he's running and the body keeps running, has to eat on plates that keep the food carefully separated. When Sula visits his shack for the only time, what strikes her is not that it's a shack but that it's incredibly neat. It's as neat as Helene's house. Shadrack loves order. He loves order, because he's seen chaos. Plum is the victim of war. He's a man who goes backward in his life because he can't deal with the world as it is. Jude seems to feel that the world is at war against him personally until Sula, in a wonderful act of signifying, says, "What are you talking about? The whole world loves black men.” She laughs: “[White men] spend so much time worrying about your penis they forget their own. […. White women] chase you all to every corner of the earth, feel for you under every bed [….] Colored women worry themselves into bad health just trying to hang on to your cuffs. [….] And if that ain’t enough, […] Nothing in this world loves a black man more than another black man. [….] So. It looks to me like you the envy of the world” (103-104).

Notions of Community

The world is—even in a place like the Bottom, the wonderful community in that first paragraph—an unsafe place. It's a place where people like Jude need someone like Nel, because he feels he cannot deal with things on his own. The threat is too much against him. He needs the sacrifice of Nel, to make Nel nil or null, in order to have himself. Manhood is shaped in this book by war and by notions of war. Unlike in Hemingway’s fiction, for example, war can only be destructive. There is no possibility for the black men in this novel to have "grace under pressure," to use Hemingway's phrase, because that's not what's tolerated for black people.

To go back to the notion of community, to come at it from a different angle, one of the things that happens in Paradise is that rituals help to define community. The same thing is true in the Bottom. National Suicide Day makes sense to people in a world in which death is a more or less regular occurrence, in which the world is threatening, in which men like Shadrack and Plum come back destroyed or at least shattered. It enables the possibility of some kind of meaning, some kind of order. Don't forget that this is a community that began as what Morrison labels at the very beginning “a nigger joke” (4). One of the questions I ask my students is why is the joke given that label? Who is the joke on? Who tells the joke? Who do they tell it to?

We might say that the story, the legend that is the founding of the Bottom, is simply a story about how. The white man says, "Do this work, and I'll give you some Bottom land." The black man does the work, and the white man points to the top of the hill and says, "There's your land." The black man says, "I thought this, in the valley, was bottom land. That's up in the hills." The white man says, "That's from an earthly perspective. What that is up there is the bottom of heaven." So you get the highest point named the Bottom. The real question, not a rhetorical question, is, Who's the joke on? Who would tell this joke as a joke, not merely as a folk legend, but as a joke that people would laugh at? It shows blacks as foolish, even incompetent with the language. The master can very easily play mind games with them. Any other options? Are there any reasons that black people would keep this story alive? It can become a cautionary tale, a story on ourselves. Look at what can happen if you don't pay attention. It also quite possibly is a parable. Remember the joke, at least in part, is on the white man. It does turn out to be, in some sense, the bottom of heaven.

That story becomes part of the ritualizing of community, just as National Suicide Day becomes part of the ritualizing of community. If everything is against you, one of the ways to exercise control is through naming. One way to control the reality of death is to create a day where you say, "Let's get all the dying over with now." You'll notice that near the end of the book, the name becomes the truth. The people all go down to the tunnel on National Suicide Day, and they are destroyed. This is a community that reads signs.

One of the best ones is Sula's birthmark. What is it? Everyone sees it differently. How do people see it? As a copperhead, ashes of her mother, etc. It can't be simply a defect. It has to have a meaning. Even in the chaos that is the world of American racism in the 1920s and 1930s, there has to be meaning. If it's not immediately available to us, we construct it. Sula's mark must say something. It must be something. There is nothing random in the world. Remember the day of Hannah's death. Eva looks back and has the seven odd things: the dry wind, Hannah's question about love, "Did you really love us?"; Hannah's dream of a red wedding dress, and Eva said, "I should've gotten that one right. I should've known what that one meant." Sula's causing trouble with the Deweys, who she mostly never pays any attention to. Then the missing comb. "If I could've read the signs, I could've changed things. I could've prevented this outcome." That means there are signs that can be read, not just random events. You could only read them backwards. If you could read them forwards, then there would be no trouble. We can't read them forwards, so we go back.

Sula arrives. This brings us back to the notion of community and how community relates to individuals. Sula comes back after years away. People start noticing things. When you get to Paradise, there are all of these things, these events going on which are not normal, or at least the men of the town are claiming that they are not normal. “Let's find an explanation for them,” they say. “Let's read the signs.”

Scapegoating Sula—And Its Consequences

When Sula comes back, there is a plague of robins; the child that falls down the stairs…. There is a whole series of things. The Bottom residents conclude that Sula must be responsible. “Sula, whom we never trusted, who had the audacity to leave us--Sula must be responsible.” What happens is amazing. By creating a scapegoat, by blaming Sula for all the problems of the community, they can then become a better community. Women take better care of their children. Men and women are more attentive to each other. The community comes together in self-defense against the evil. Morrison is preoccupied with the notion that evil is necessary for virtue in the world. If you don't have an embodiment of evil, then you start messing around. You're negligent of others, unfaithful, and you're resentful. When there is something to be against, then we can all get together and be against it. We can be better than we normally are. They create a community or a set of community values around the antagonism of Sula, the way an oyster forms a pearl around the irritation of a grain of sand. When Sula dies, they fall apart. That's the proof. They can't do it on their own. They need her.

This is a fun piece. Shadrack goes through the fire of war. What happens to him? What happens to this Shadrack? He is destroyed by the fire, not strengthened by it. Eva, I've already mentioned as the mother of everyone, as the source of both temptation and death. This is Eva who has eaten the apple and liked it. She isn't afraid of anyone.

Eva says that Sula looked interested when Hannah burned. She didn't look terrified or shocked. We don't know Sula's response. Eva clearly thinks that Sula is demonic. The mark is a snake. Sula, on the other hand, knows that Eva killed Plum. She's afraid the same thing will happen to her. These are women who are terrified of each other. Sula's resolution is to send Eva away. To me, there are lots of reasons why one could justify sending Eva away.

Naming

Morrison plays a lot with names. Look at this list of the men. Besides Shadrack, a biblical figure, we have:

(1) BoyBoy

(2) the Deweys—that might be an echo of Faulkner and the Snopeses

(3) Chicken Little—and it's an inverted Chicken Little story because the chicken falls into the water rather than the sky falling on the chicken. (The funeral of Chicken Little and the way the women are described in that passage is another instance in which they engage in what is almost the daily confrontation of death in their community.) Except for Shadrack and Ajax, who is the mythological figure, the superman—Albert Jacks is just an ordinary name, just a more or less ordinary man, which Sula doesn't get until it's too late—all of the male characters have belittling names.

One of the things that Morrison did, especially in the early novels, was that she had certain female characters' names end in "a." She's very consistent about this. We have Claudia and Pecola in The Bluest Eye and Sula, Hanna, and Eva in Sula. Then she has another set of female characters whose names end in consonants, usually "n" or "l." They seem very different. The “a” characters are always key sympathetic kinds of characters.

The Novel’s True Protagonist

Back to my question, Whose novel is this? This is a real question. One of the things that Morrison is suggesting is that women, especially black women, are the necessarily substantial people in the world. I try not to claim that Morrison is saying, or means, or the truth about this Morrison novel is . . . But I think the suggestion here is that black women are the substantial figures in the world and necessarily so. Don't forget that this is a novel—like The Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon, Jazz, Paradise—that is primarily about black people. The worlds of those novels are African American worlds. They are not worlds in which there is extensive interaction between the races. The white presence in The Bluest Eye is an abstract image. Morrison creates African American worlds. In that framework, she's saying it is the women who sustain the world for better or worse.

We read Eva as Eve, or we can read her as evil. She murders her own child. You can't call it anything other than murder. You want to be careful about dealing with mother/child relationships in Morrison. There is nothing sentimental about them. There is very little that is happy about them.

On the one hand, we get Eva's feelings about why she's doing this, but on the other hand, there is a deliberateness about it. She's very precise about what she's doing and how she's going about it. She does assume a god-like role. I would argue that this whole process of naming is a god-like role that she is playing in the book. Eva assumes that status and that's her flaw. She presumes that she can make the world over in her own image. Getting her leg cut off and then her not being able to save her own daughter, the child that she does seem to really love, plays into that perfectly.

You've evaded my question long enough. Whose novel is this? If the way we determine a central character is by the changes in that character, if that's the character who undergoes change or transformation, then we can argue that it's Nel’s story. Nel is the one who early on is trying to be someone like Sula or trying to create a hybrid personality. She does this in resistance to her mother. Then she submits to community values and sacrifices herself to creating Jude. When Jude fails her, and she has that passage about the empty thighs, she has reached the very bottom. In a conventional sense, she reemerges as the perfect conventional woman. She becomes an important part of the church and community. Then Sula dies and she seems to deal with that. She continues to blame Sula for what she has been forced into, the discovery of her own strength; that is, she can, in fact, survive without Jude. She holds Sula responsible for forcing her into that position. Then we have her confrontation with Eva, where Eva in another one of these moments of magical realism, says, "You just watched when Chicken Little died…. You just watched. You did nothing. It was easy to blame Sula, but what about you?"

On the very last page:

Suddenly Nel stopped. Her eye twitched and burned a little.

"Sula?" she whispered, gazing at the tops of trees. "Sula?"

Leaves stirred; mud shifted; there was a smell of overripe green things. A soft ball of fur broke and scattered like dandelion spores in the breeze. [This gray ball now has become seed.]

"All that time, all that time, I thought I was missing Jude." And the loss pressed down on her chest and came up into her throat. "We was girls together," she said as though explaining something. "Oh Lord, Sula," she cried, "girl, girl, girlgirlgirl."

It was a fine cry—loud and long—but it had no bottom and it had no top, just circles and circles of sorrow. (p. 174)

Nel's revelation: It was never about Jude. It was always about Sula. I think we could contend that at the end of the book, "Oh Lord, Sula," is a prayer. If Eva could be god, why not Sula? Sula can be seen as Nel's hero in some sense, the one who stands against the rest. She's the one who has the courage to die alone. We have to deal with the implications of Sula dying—apparently of cancer. Are we supposed to read this symbolically? Is all the terrible stuff that Sula has done in her life symbolized by the disease that kills her? Isn't that turning it into a sign? Isn't part of the point of the book that we have to be careful about reading signs? Maybe why men like this book is because they get to have Sula as the hero. It's all right for heroes to die. A hero who has challenged convention, who has taken on the whole world, and the instant she dies, she has a laugh. "Wait till I tell Nel."

Sexual References

Now let's talk about sex. We've talked about death. One of the things that strikes me about Morrison is that there's a lot of reference to sex. There's a lot of eroticism and sensuality, but there's relatively little depiction of sexual behavior. The key scene here, of course, is Judeand Sula in the bedroom. Are they engaged in sex? It's clearly sexual play, but is it sex? Again, if we're going to be careful about how we define gender when dealing with Morrison and gender identities, we also need to be careful about assuming that certain things are happening. One of things that might be going on in that scene is precisely sexual play. That is not intercourse. That's something that might lead to intercourse or might lead to a few moments of erotic experience that doesn't lead to intercourse.

Another thing we can do is loosen our notion of sexuality. Look for the number of scenes in which Morrison actually describes acts of sex. They're pretty rare. She uses language about sex. She makes generic observations about sex—that Hannah needed to be touched every day and that it took place in the pantry. Then she turns it into this little joke about not sleeping with anyone. We need to consider that. We also need to consider Sula's defense and whether we ought to take Sula's defense seriously. People dismiss it out of hand. Sula says nobody owns anybody else. "You don't own Jude; he doesn't own you." She posits that we are all free agents. If we don't think of people as property, then it raises all kinds of questions about how we describe human relationships.

For Nel to marry Jude in order to make one Jude, that makes Nel an object or maybe a parasite. Or maybe Jude is the parasite. Women traditionally took the last names of their husbands because implicitly they were the property of their husbands. Women were literally the property of their husbands throughout much of human history. Children were the property of their fathers. What if people aren't property but are truly free agents and can make their own choices not once in a while but daily, from hour to hour, minute to minute? Why shouldn't Sula engage in sexual play with Jude?

I want to propose to you that Morrison in some ways may speculate more radically about relationships than we like to think about. It's fine when she's playing games with magical realism, she's messing with time, and she's creating weird characters. But what happens when she offers to us through the perspective of a character that she represents sympathetically—because whether we side with Nel or Sula, Nel says it's Sula at the end that mattered. She allows Sula, who is the most intelligent character in this book, to speculate about the nature of human relationships and about different ways to organize human relationships. All I'm suggesting is that she's speculating. She's offering us a view that is fundamentally different. Morrison has also subverted Nel's perspective on things repeatedly throughout the book, including at the very end where Eva, who, generally speaking, speaks the truth and usually speaks painful truths, in effect says that Nel has been so self-righteous. Because Eva insists, “You watched” (168), she implies that Nel let Chicken Little die just as much as Sula did. She implies: “And you were worse. Because at least it mattered to her.”

If Nel's position is being undermined, at least some of the time, and Sula's position is sometimes being supported, I would suggest that we might want to take seriously any number of notions put forward by a character like Sula. Not because they will make us think a little bit, but because they will make us uncomfortable. Let's ask the most basic kinds of questions. Do we think about people as property? Do we think about relationships as ownership? If we do, then could it be possible that we ought to rethink that question?

Morrison does not offer readers the explicit answers: she's a novelist, a fiction writer; she's not (most of the time) an essayist. She offers all kinds of propositions in her nonfiction, often outrageous ones. For example, consider the question of whether we should be worrying so much about teenage pregnancy, because until the twentieth century, by and large, all pregnancies were teenage pregnancies. Let's stop getting anxious about the wrong things, she says, and look at what might be real issues or other ways of considering the issues that we keep looking at. In Sula, we find many of these real issues. Morrison’s allowing Sula to propose things that no other character has the audacity to propose. She uses her most liberated character in some sense—and in some ways her most irresponsible character—to pose these issues. Don't tell your kids this. Keep it a secret. This is our secret.