| Language Matters Home | Language Matters I | Language Matters II | Language Matters III | Language Matters IV |

| Discussion Board | Resources | Novel Discussions | |||||||||

| The Bluest Eye | Sula | Song of Solomon | Tar Baby | Beloved | Jazz | Paradise | Love | A Mercy | |||

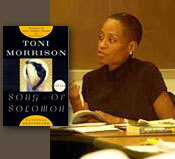

Song of Solomon

Dr. Giselle Liza Anatol is an associate professor of English at the University of Kansas. Her areas of specialization include contemporary Caribbean women's literature, African American literature, and children's literature. She has published an edited collection Reading Harry Potter: Critical Essays (Praeger, 2003), and numerous articles on representations of motherhood in Caribbean women's writing. Professor Anatol has lectured on the works of Toni Morrison to high school students, junior high and high school teachers, and delivered papers on Morrison's work at academic conferences. She was a Conger-Gabel Teaching Professor from 2001-2004.

Novel Discussion

As I mentioned in the Bluest Eye session, the stories that Morrison is telling are not easy stories—she confesses in that 2001 CSPAN interview that she is taking you for a “bumpy ride”: the novels have difficult history and subjects. She wants you to confront them with your eyes open. The idea of crossing over a threshold into this space of awareness is addressed in the e-reading article "Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature." As I mentioned earlier, although the essay is complicated in places, it is well worthwhile for a better understanding of how Morrison views American Literature and her place within it.

To review: Morrison begins "Unspeakable Things" by talking about literary canons. She observes that “There is something called American literature that, according to conventional wisdom, is certainly not Chicano literature, or Afro-American literature, or Asian-American, or Native American, or . . . It is somehow separate from them and they from it, and … this separate confinement, be it breached or endorsed, is the subject of a large part of these debates.” (1) In many ways, Morrison’s fiction has acted as a bridge between Black writing and the American literature that for years was taught only as works by dead white male authors. At the bottom of that second paragraph, Morrison mentions how a "temporal, political, and culturally specific program” can (and by extension, has) comes to constitute “an eternal, universal and transcending paradigm." We must be aware of how a particular experience, whether that be a middle class, white, and/or male experience, has come to represent what's universal—what everyone understands and recognizes. Is it universal because it is truly common to all people, or is it universal because these are the books that are celebrated, and taught in schools, and held up as the signs of a good education? The literature from this singular perspective is what has commonly been put forth as great literature, as The Classics. Again: in the third section of the article where Morrison talks about the first line of each of the novels, the themes that consistently come up are:

1) Community, both for its intimacy and strong sense of support in the lives of the characters but also the disruption caused by people who refuse to come to flock, walk along the same path that their community calls for, or who speak out in certain ways and challenge the tribe. There is this powerful tension of between what it means to be bound to a people and to be bound by other people. One can feel bound to people, connected to them with lots of loyalty and support, but there is also the sense of being bound as in being tied up and constricted. Those issues of inclusion and exclusion get brought up numerous times in all of Morrison’s work.

2) African American Vernacular Traditions: oral histories, folktales, songs and ring rhymes, riddles, the dozens (a verbal competition of insults). Song of Solomon is very concerned with the loss of these traditions and the desire to bring them back.

3) Gender Identity and Gender Construction. Think about Ruth’s relationship with Macon, the opportunities available to First Corinthians and Magdalene, Lena’s criticism of Milkman and the privilege that accompanies his “hog’s gut” (215), and Hagar’s relationship with Milkman and how this affects her sense of worth. There are many other examples, of course; these are just a few to get you started.

4) Black Migration. That would include the forced migration of enslaved peoples from Africa to the Americas during the slave trade and also voluntary migration in terms of escapes from slavery and the huge mass of people who moved from the South to northern cities during the Great Migration. In the Foreword to Song of Solomon, Morrison talks a lot about migration. (Much of the Foreword comes from the assigned sections of "Unspeakable Things Unspoken," by the way.)

5) American Citizenship. In that Foreword, Morrison describes specific African American history and also the larger US history and how different groups that make up US culture fit into that. There is a piece of her discussion of the first lines in "Unspeakable Things Unspoken" that is not included in this Foreword to which I’d like you to pay attention. The paragraph begins with "The journalistic style" (p. 28).

She's talking about Song of Solomon's simple words and uncomplicated sentence structures. It is an attempt to echo journalistic style, but it is also highly oral syntax, suggesting African American oral traditions: “the ordinariness of the language, its colloquial, vernacular, humorous and, upon occasion, parabolic quality sabotage expectations and mask judgments when it can no longer defer them." So we have a blend—the written and the oral. And then comes a part that I think is striking: "The composition of red, white, and blue in the opening scene provides the national canvas/flag upon which the narrative works and against which the lives of these black people must be seen…." As you remember, the opening scene has the red petals that the girls have made that are fluttering all over the white snow and also the image of the blue wings. There's repeated reference to the blue wings. That's very intentional, the red, white, and blue imagery. Morrison goes on to state that this national canvas—this ideology of American patriotism, and mainstream conceptions of what it means to be American—“must not overwhelm the enterprise the novel is engaged in. It is a composition of color that heralds Milkman's birth, protects his youth, hides its purpose, and through which he must burst (through blue Buicks, red tulips in his waking dream, and his sisters’ white stockings, ribbons, and gloves) before discovering that the gold of his search is really Pilate’s yellow orange and the glittering metal of the box in her ear."

There’s a lot going on there! She uses those colors, thrown in here and there, to vividly describe scenes, but also as a part of this larger project that she's engaged in—a critique of American society and the ways that African Americans are asked to participate but are also excluded in different ways.

The next paragraph is when she says, "These spaces, which I'm filling in, and can fill in because they were planned, can conceivably be filled in with other significances.” She's talking about what her intent was and what she was thinking of as she was writing, but also the room and freedom she allows for the reader to move about in the narrative, and think, and ponder, make connections, and draw her own conclusions. There really is this wide open sense of what individual readers will bring to the narrative.

In this light, I’d like to begin with the theme of names and naming in the novel. Let’s start with our own names. What does your name mean? That can be your first and/or last name. You can choose one or both.

Participant: It seems like every third or fourth girl born in the Midwest in 1962 must have been named Susan.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: So there is the idea of a generation and culture.

Participant: I think it's the opposite of what's happening in Song of Solomon.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: OK—we'll come to the novel in a moment. I'm thinking of the year I was born, which was 1970, and that year Jennifer was the most popular name because of the movie Love Story. A few years ago Ariel was the most popular name for girls because of Disney’s The Little Mermaid. The choices of names speaks to a particular time, but also to social conventions. It seems to me that you're talking about a struggle—the individuality that your first name is supposed to give you but that you didn't get.

Participant: Arthur means strong as a rock. I shortened my name to Art, a form my older sister and mother have never used and never will.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Names and ancestry show your position in a line of people and illustrate the idea of your parents, or whoever names you, wanting to connect you to others; however, you were determined to find your individuality. There is a tension between belonging to a group and seeking a sense of one’s own self. Blending the past with the present and the future, this bestowing the name of an ancestor or a historically significant name respects and honors the past members of the family but also illustrates the traits, hopes, and dreams that the parents are trying to pass on to the child for the future.

Is there anything else a name can tell us about a person or other ways that names function?

Participant: My name is Gladys. Gladys is a very old name, so all the people I know who are named Gladys are either very old or dead. I was named after my aunt. I always spelled my name Gladys. But when I got married and went to get my birth certificate, it was spelled Gladdie. Back in that time, you could change your name to the correct spelling.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: We observe here how the name Gladys is supposed to mean something specific—a connection to your aunt—as it was transferred to you, but your later reading of the misspelling of it opens it up and explodes it in different ways.

We might talk about last names too.

Participant: My first name's Linda, which means pretty. My last name is Dobratz, which is Polish for good. So I'm "pretty good."

Dr. Giselle Anatol: That’s funny! But you’ve allowed us to weave migratory, national, and ethnic histories in. There’s your individual family history but also this larger history. Can you see how that works?

Participant: Your name extends your tiny self to larger historical and social forces.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Yes. And how those all connect together. You were talking about “Dobratz” and how that connects you to a specific cultural and ethnic group. It might work in terms of religion as well. A name like Steinberg is identifiable as a Jewish last name.

Participant: I have the same thing, a name connecting to my ethnicity. Ryker was my maiden name. It was supposedly shortened from the name “Von Rykenberg” when my ancestors came. I thought the way the name was shortened was interesting.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Ethnicity and culture are either explicit or hidden. Names were shortened for assimilation purposes. We'll talk more about that when we discuss this book and about names that are changed as people move through the system.

The history of my name resonates with a lot of the stories that you are telling. Giselle in the US/American context is very unique, but in Trinidad, which is where my family is from, Giselle was a name like Jennifer of the early 1970s—everyone had that name. Walking down the street there, if I'm visiting family and someone yells out "Giselle," I'm always turning around thinking it must be me, having grown up in New Jersey, but six people will turn around. So I belong to an ethnic or cultural group in one context, but my individuality is highlighted in another. In terms of my surname, all of the Anatols in Trinidad are closely related. My sister and I have done searches for the Anatols in the United States, and we've found we're all closely related. There's that idea of being able to identify someone as kin simply by hearing a name. But it also suggests, farther back, a painful history, because Anatol was the name of slaveholders. The original names of African ancestors farther back is unknown. I think of that in terms of race and culture, but also we might think of it in terms of gender. My name, Giselle Anatol, does not account for my mother's maiden name at all. It's nowhere there or in the names of any of my siblings. Most of my mother's brothers have not had children. There won't be a passing on of that name. Consider the ways that names perpetuate history but also the way a name is often lost.

Participant: My first name is Vicki, and it was chosen by my father. He was very adamant that it would not be Victoria. I'm very surprised that I wasn't named Debbie, because he was in love with Debbie Reynolds. I grew up liking Vicki, because there weren't that many Vickis, although it seems like a common name to me.

The Symbolic Significance of Names in the Novel

Dr. Giselle Anatol: This exercise is valuable, because so many people do not think of what their names mean or they may only think of their names in passing. As you see, it generates great discussion, interesting stories and memories, and lots of connections that can be made to the book. What are some of the specific instances in the novel that deal with names, and the processes of naming, unnaming, and renaming?

Participant: Milkman's nickname: his nickname brought shame when he found out why he was named that.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Think about the burden of a name when you know its negative history. When you question Milkman's nickname, you're seeing it as something that was burdensome to him.

Participant: Especially as he decided what the connotation was.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: The derivation of this nickname makes one read it as negative, but I would argue that Morrison does not cast it as exclusively negative. It is not simply a matter of good or bad. Giving the nickname suggests a sense of intimacy, and not the exclusion that he might suffer in other contexts. What do you think?

Participant: The father refused to use that name, and it made him dislike his son.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: When Freddie gives him the nickname, is it meant to only shame him and the family?

Participant: I think it's a deliberate reminder to Ruth about what she's done all these years. I think Freddie's getting back at her.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Let’s look at that scene (p. 14). He's howling and laughing and struggling for a better look through the evergreen tree. He comes around and enters the house. He feels a sense of agency; he has gained the upper hand, even though he definitely does not have social and economic power in comparison to the Deads. Then he says,

". . . you don't see it up here much. . . . " But his eyes were on the boy. Appreciative eyes that communicated some complicity she was excluded from. Freddie looked the boy up and down, taking in the steady and secretive eyes and startling contrast between Ruth’s lemony skin and the boy's black skin. “Used to be a lot of women folk nurse they kids a long time down South. Lot of 'em. But you don't see it much no more. I knew a family—the mother wasn't too quick, though--she nursed hers till the boy, I reckon, was near ‘bout thirteen.…"

This last part is an insult to Ruth by association, but what does Freddie’s discovery do to Milkman? What's going on there? What is that about his “appreciative eyes that communicated some complicity” ?

Participant: He's thinking the boy's enjoying this.

Participant: Look at what Freddie says on the top of p. 15. He says, "A natural milkman if I've ever seen one. Look out, womens, here he come."

Participant: Milkman realizes through Freddie's reaction to what he's seen that what he has suspected all along is strange and wrong.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: There's something strange; there's something wrong, but the power dynamic is key. All of the fault is put on Ruth, so that she's incredibly disempowered at that moment. Notice, though, that Milkman is given a certain amount of power, and the power is specifically linked to his gender. His position of male privilege is heightened and highlighted throughout the text.

Participant: His mom changes at that point too, because he talks about wishing that his mom would look at him as he stands there. He's not the protected young baby anymore. Now he's on the outside, and his mom's reaction has pushed him aside a little bit.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Yes—It serves to alienate him from his father, as we were talking about before, but also from his mother.

What other names do you think are significant and might link to what we've been talking about?

Participant: Macon Dead—his last name. This symbolism is so clear and how he has experienced a sense of death, to a sense of dying inside.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Which Macon are you talking about?

Participant: Junior.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Milkman's father. Interesting. Guitar tells him [Milkman] about a third of the way through the text to live his life. Don't just be a walking dead man. Here we have the idea of escaping the name but also escaping that inherent quality of death.

Participant: Can we talk about where the name comes from? It is ironic that historically this man who was finally freed from slavery had the one thing he owned stolen from him—which was his name—and was given the name Macon Dead.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Good point! That displacement of the name is complicated. An early passage describes all the stuff that's built into Macon Dead’s name in terms of the notion of death. On page ten and eleven where the family is being introduced, there is the description of bright lifeless roses that the girls make. That's all they do: sit and make these lifeless roses.

It was not peaceful [the quiet of the house] for it was preceded by and would soon be terminated by the presence of Macon Dead.

Solid, rumbling, likely to erupt without prior notice, Macon kept each member of his family awkward with fear. His hatred of his wife glittered and sparked in every word he spoke to her. The disappointment he felt in his daughters sifted down on them like ash, [that makes me think of ashes to ashes] dulling their buttery complexions and choking the lilt out of what should have been girlish voices [note that imagery of strangulation and choking]. Under the frozen heat of his glance, they tripped over doorsills and dropped the salt cellar into the yolks of their poached eggs. The way he mangled their grace, wit, and self-esteem was the single excitement of their days.

I love the way that Morrison flips the phrases. That's stirring writing: the unexpected twist when Macon’s brutal, mangling presence elicits not hatred, or terror, but the ironically positive emotion of excitement out of the girls. So . . . Macon has not only died but creates death, the strangulation of wife and daughters, the death that permeates the house.

Let’s look at the scene about the drunken Yankee (p. 53). The one thing that Macon Senior, the “first” Macon, has—his name Jake—is taken away from him by this Union soldier. The Northerners were supposed to bring freedom to the enslaved Southern blacks, and yet this man could not care less about the person standing in front of him. How do we tease this out even further? Are there any other ironies to the fact? Do we read it entirely negatively? Why does Jake or Macon Dead then keep the name when he's given it on these official papers? Why not still go by Jake? What's at stake here?

Participant: Part of it is the idea that he can, listening to his wife, sweep away the painful past—his history as a slave. Let's just get a clean break from the past. Of course, that's antithetical to the themes of the novel.

Participant: He wanted to wipe out the past.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Yes. It gets complicated: wiping out the past would remove the name that he knows and that he identifies with and responds to—his identity up to this point. At the same time, it would be a name that had erased a previous name. Macon “Junior” (Milkman’s father) does talk about that. When Macon is thinking of names (17-18), he's walking and he hates the fact that Milkman has been given that nickname. "Surely, he thought, he and his sister had some ancestor, some lithe young man with onyx skin and legs as straight as cane stalks, who had a name that was real. A name given to him at birth with love and seriousness. A name that was not a joke, nor a disguise, nor a brand name."

He's seeing this original African figure as the ancestor. The problem comes when we learn that one of the ancestors, Heddy, mother of Sing Byrd, or Singing Bird, and Crowell Byrd, or Crow, is Native American, not African. Sing’s and Crowell’s biological father is unknown. Is he white? European? American? or is he African or African American? or is he also Native American? That notion of going to an originating root is revealed as a fiction in a particular way. It's not always so clean. Morrison is speaking to the problems of lost history, that result from the experience of enslavement.

Is there anything else about this scene of the renaming by the drunken Yankee soldier that you found strange or peculiar?

Participant: I was thinking about renaming in general.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Consider Milkman again—the ways that his names reflects his experience, but also that being named connects him to people. Even though Macon hates the fact that nicknames are given, it shows that Milkman has a position in this larger black community that Macon doesn't have. Macon is so alienated and isolated that no one would ever give him a nickname. No one ever rides on the Packard. There are no little kids on the bumpers, there are no teenagers asking for a ride, no one hails him, no one says hello. They are totally isolated in this bubble because they have no connections to community. Is that the same thing that’s going on with Jake/Macon and the soldier?

Participant: Isn't there some significance that it's a drunken Yankee that gives him the name?

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Yes. What do you think it is?

Participant: Is it lack of ownership? If he wanted to wipe out the past, he could rename himself, but he lets a drunken Yankee do it. He accepts it. That's still not ownership.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Exactly. Think about the idea of power and what it means to name someone. In many ways, the soldier’s act is replicating the slave system where the slave masters were naming their “property.” Milkman and Guitar reference this during the 1960s, when Milkman says, "You sound like that red-headed Negro named X. "Why don't you join him and call yourself Guitar X?" (160). But Guitar rejects that premise of wiping away the slave past. He's saying that this slave owner’s name is part of his history and experience:

“I don't give a shit what white people know or even think. Besides, I do accept it. It's part of who I am. Guitar is my name. Bains is the slave master's name. And I'm all of that. Slave names don't bother me; but slave status does."

In certain ways, he's saying that names don't matter; they’re just the outer covering. Is there any other place where we see that perhaps names don't matter?

Participant: Macon Jr’s sister is named Pilate, who was the killer of Jesus. Yet she’s the one who has the most life in the whole novel.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: A sense of self-worth.

Participant: She plays by her own rules. At some point she takes the power for herself and invents her own life. In that way she becomes “pilot”—the homonym for her name, Pilate. She's directing her own path.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: She is claiming that history by putting the name in the box but not letting it direct her. She directs her own self through her life.

Another name that we might mention is Not Doctor Street. The name opens up the narrative (4). What did you think of that? Are there any other ideas that come into play? Mercy Hospital versus No Mercy Hospital. What's going on there?

Participant: They both reflect negativity. Not Doctor and No Mercy hospital emphasize the negative aspects of that community and that structure—those people are denied mercy at that hospital. They're denied everything at that hospital.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: The denial of access in a larger American system. The name Not Doctor Street comes from those official notices that say, "No, this is Main Street”—as it's acknowledged by the post office, as it's acknowledged by the recruitment office, all of those official European American-run institutions.

Participant: It's wonderful how they use that to avoid the draft. Everybody puts down Not Doctor Street, and no notices ever come. They use their own system to fight the bigger system.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Subversion of the system.

Participant: They subvert it by the simple use of the name Not Doctor Street.

Participant: I like that—Not Doctor Street—they turn the negative denial into something positive. The doctor got to remain in the street because they called it Not Doctor Street. They got to keep that doctor.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: It's not a restructuring of the system, saying this is unfair, we demand change. The system is still definitely in place, but there's this constant subversion working beneath the surface. We might think of that situation in terms of written tradition versus oral tradition as well. People in charge—the politicians, the media, educators, etc.—have control over the written word, over literacy, and that idea of literacy comes up powerfully in the case of Jake, who gets turned into Macon Dead, because he can't read. The soldier is writing all of the wrong things in the wrong places, but the former slave can't read it because he doesn't know how to read. He has been forbidden to learn how to read and write in slavery. Later, he signs away his farm, because the local white farmers and landowners present him with a written document, and he can't read it. The power associated with writing is something important to recognize. This African American community uses part of their culture—the oral traditions that are so strongly a part of their culture—to undercut the system.

Participant: It’s interesting that Pilate's name is the only word her father ever wrote.

Biblical Names

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Some people have called this book Morrison's most literary. There are many allusions to different texts and traditions. One of those is the Bible. What might Morrison be doing in her numerous references to the Bible and to biblical names? What might be the significance of the ones she chooses? She has spoken about the ways the church helps ease the pain and suffering. Her use of the names reflects the strong connections people have to Christian churches in the African American community. There seems to be a lot of symbolism at play as well, though.

Participant: Her use is the opposite of what they do in the Bible. Ruth is someone who is very loyal in the Bible, but in Song of Solomon Ruth is not loyal to Macon. Pilate is the betrayer of Jesus and controls someone else’s life, but in Morrison’s novel Pilate ends up being in control of her own life. Hagar was a prostitute in the Bible but became obsessively faithful to Milkman in the book. . . . It’s the opposite of what they are in the Bible.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: I’d like to pick up on that idea of Pilate is as the betrayer of Christ in the Bible. Pilate in Song of Solomon is definitely not Milkman's betrayer, but rather his savior. Macon thinks that she had betrayed him, but that's his version of history, his misperception of what has happened. She's not associated with betrayal in any way. What might that inversion say about how Morrison perceives Christianity or church doctrine?

Participant: Pilate transgresses all of these social conventions. Pilate listened to the crowds in the Bible when they demanded that Jesus be crucified. Morrison's Pilate totally ignores what society says that she should do.

I love those descriptions of Pilate’s family, as opposed to Macon’s. They don't eat at the table. They don't serve dinner. They eat out of the pot. They eat whatever they have.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Remember the emphasis on choosing names blindly in the Bible, not with any thought or reading into the text to see what the stories are and trying to associate a particular ideal with a particular person. Flipping through and saying, "My child's name will be Exertion”—that's not the way that you read or understand. That can become problematic blind faith, or problematic adherence to the ways things have always been done.

We need to take Guitar's statement into consideration. There is no possibility at this point to go back to some kind of original African religious practice. African American culture is a combination of cultures. Even though Christianity has been used to discipline, squash, and quell the original cultures, it still is a powerful part of people's religious belief and practice. Again, we need to note the tension and the history.

The next theme I'd like to address is journeys and flight.

Participant: Before we go further, if someone addresses the biblical Song of Solomon, what do you say? It's all about love.

On Love and Contortions of Love

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Yes—Morrison’s title overtly refers to the “Song of Solomon,” or “Song of Songs,” in the Bible. Sometimes the “Song of Solomon” is taught as love poetry. Notions of love and distortions of love are some things I often think about as I'm going through the book. Consider, for example, the relationship that Macon and Ruth have originally. There's that great scene of how he loves to undo the corset and her boots. There's talk of them laughing and giggling. It's not that they always hated each other. They once did love each other, but that completely dissolved. The relationship between Hagar and Milkman gets violently contorted from strangers to cousins to lovers to predator/prey, and the relationship between Macon and Pilate—that incredibly loving and affectionate sibling relationship—falls apart. There are numerous references to what people define as love.

Remember when Pilate takes the knife, and she holds it to the man's heart after he's beaten up Reba. There's talk about women being weak and foolish: “Women are foolish, you know, and mamas are the most foolish of all…. Mamas get hurt and nervous when somebody don’t like they children…. We do the best we can, but we ain’t go the strength you men got. That’s why it makes us so sad if a grown man start beating up on one of us” (94). Pilate stresses the protective love of parents for children, specifically mothers for children, but the novel also depicts powerful bonds between fathers and children, such as the presences that continue to haunt both Ruth’s and Pilate's lives. Note all of these different configurations. Does love mean belonging to someone? When Hagar falls apart, Guitar tells her that love is not owning someone. Love does not mean belonging to someone. “It’s a bad word, ‘belong,’” (306). Love does not mean that you fall apart when the person leaves you.

Participant: What about Guitar talking about love in those words that Milkman remembers during the skinning of the bobcat?

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Guitar is talking about love as a motivating factor for the Seven Days. We can talk about the Seven Days later, too, and what their group means for political activism and race relations. Guitar keeps on saying it's about love. Is that another distortion of love? Is it empty words?

Participant: Guitar loves the black community, but won't embrace the whole American community, which is inclusive of whites. I think that's why his quest fails. Milkman is ultimately better because he is embracing the whole community, including women and Native Americans and whites—all of his potential ancestors.

Participant: I wondered about what his name meant. Guitar. When you think of a guitar, there's a certain strum on a guitar that comes around. In some ways Guitar is a flat character in that he doesn't change. This is his refrain, and it keeps coming back. It keeps playing in Milkman's head.

Participant: His name is what he wanted but couldn't have. When we talked about names, in his case it was what you are deprived of.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: The idea of not what you have but of what you don't have. That question of desires that can't be held onto but are always fleeting.

Participant: But he can't play the guitar—his name is inaccurate.

Participant: So maybe Guitar’s perception of love is also inaccurate—it is a distortion of love.

Participant: Do you think the novel’s title somehow combines Milkman’s great-grandfather's original name of Solomon and his grandmother's name, Sing? I don't know exactly how that translates.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: African American culture, and all American culture, is a combination of all of these different traditions, even though that's not usually acknowledged. If you type in Song of Solomon on the Internet to do a search, many of the links that come up will be biblical. Looking at the title originally made me think this is only about the biblical allusion, but within the narrative there are allusions to African traditions, such as Solomon’s act of flying, and references to the Native American history and culture in the character of Sing. Your proposition works well!

Participant: Before we leave the names, we need to talk about Circe.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Great! That's where I'm going.

Journeys—Physical and Psychological

Participant: The idea of the inclusion of all cultures in her canon of literature—she doesn't care where she's pulling from. If it works for her, it works, and she's going to use it.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: I'll give you a quick quotation that relates to the theme of journeys for another clue as to what Morrison is doing. In “Rootedness: The Ancestor as Foundation," she says, "The autobiographical form is classic in Black American or Afro-American literature because it provided an instance in which a writer could be representative, could say 'My single, solitary and individual life is like the lives of the tribe; it differs in these specific ways, but is a balanced life because it is both solitary and representative.' The contemporary autobiography tends to be 'how I got over—look at me—alone—let me show you how I did it'” (339). This is about journeys through life, and providing a path for others to follow. She draws a boundary between traditional white American autobiography that focuses on individualism and Afro American autobiography and literature, which center on the individual but are also about the community. You cannot do it alone.

We see lots of tension in Milkman's life between that drive for individualism and the communal impulse. It's especially poignant when he's going on his trip to find out about the treasure and his family. At first, when he's on the plane, he says that he wants to go alone (220). He's sorry that Guitar can't be there, but it is exhilarating to him. "This one time he wanted to go solo." But he needs help along the way. He needs the advice of Circe. He needs Nephew to drive him around Danville. He needs to borrow the car from Reverend Cooper. He needs to hitchhike and ride back with the man with the Coca Cola. He cannot succeed on his journey without help from others.

Note, too, that he thinks he can cut ties and remain completely independent by paying for “services” rather than owing people time, concern, and favors. Remember how, after the talk with Circe, Milkman says, "You should leave this place…. I’ll help you. You need money? How much?” Or when he wants to pay off Hagar and give her money. Or when he offers the man with the Coca Cola payment for the soda and the ride. Everyone gets offended because this isn’t about making money and business dealings; it’s about community and personal connections. Milkman always thinks he can buy people off and take himself out of community responsibilities. This also means that he misses out on community nurturance.

Milkman’s rebirth—his psychological journey—moves him away from being a character who has no self and who's an individualistic hero. Early in the novel, when he's looking in the mirror, he talks about having a "fine enough face. Eyes women complimented him on, a firm jaw line, splendid teeth. Taken apart, it looked all right. Even better than all right. But it lacked coherence, a coming together of the features into a total self. It was all very tentative. . . .” (69). He's very ambiguous and amorphous.

He goes from being an individualistic hero to a hero who is firmly enmeshed in the community. The hunt is important for that. They go on the hunt and kill the bobcat. He feels a sense of belonging right after the hunt (292-93).

He didn't feel close to them, but he did feel connected, as though there were some cord or pulse or information they shared. Back home he had never felt that way, as though he belonged to anyplace or anybody. He’d always considered himself the outsider in his family, only vaguely involved with his friends, and except for Guitar, there was no one whose opinion of himself he cared about. . . . But there was something he felt now—here in Shalimar, and earlier in Danville—that reminded him of how he used to feel in Pilate's house.

He is very much becoming a part of the community.

Also in the vein of journeys and epics, Song of Solomon contains references to German fairytales, such as “Hansel and Gretel,” a story about a trek into the woods and then back out (219). There are numerous allusions to ancient Greek myths, such as the myth of Jason and the golden fleece, in Milkman’s search for gold. On p. 245, Circe says, "The dead don't like it if they're not buried." Think about "Antigone" and that notion of your connection to your family versus community and abidance to the law, and the protagonist’s insistence that her brothers be buried. Also remember Daedelus and Icarus in the flight of escape. We might think about how that works.

I want to take a moment to talk specifically about The Odyssey. The Odyssey is one of the most famous and often-cited epic stories about journey. The hero, Odysseus, is tested along the way, coming back from the Trojan War. What he wants to do is find home and become reintegrated into his community.

Odysseus faces numerous adventures and obstacles before he gets back to Ithaca and battles the suitors who are vying for his wife. Consider how Morrison is employing some of these specific instances in her book, twisting them, alluding to them in various, often subtle, ways:

1) Odysseus's first challenge is a battle against the Kikonians, right after he and his men leave Troy.

2) Adventure Two is the encounter with the lotus eaters; the sailors Odysseus sends out to scout a location eat the lotus flowers and they forget all about home.

3) Next comes the Cyclops. That incident involves the one-eyed monster and the men trapped in the cave. Odysseus gets the creature drunk, tricks him with his words, and blinds him with a wooden stake.

4) The accidentally released winds from the magic bag of King Aiolos throw Odysseus’s ship off course.

5) The Laistrygonians are giant cannibals against whom the Greeks must fight.

6) Circe is the central character of Adventure Six; she is the witch in The Odyssey who turns Odysseus’s men into pigs. Odysseus has a short affair with her, and she gives him advice about how to go to Hades, the land of the dead, in order to continue on his journey.

7) In Hades, Odysseus speaks with the spirits and gets more information to continue his passage.

8) Next, Odysseus and his crew must combat the Sirens, the singing women/creatures who lure sailors to their deaths by enticing them with song to drive their ships onto the rocks.

9) and 10) Obstacles Nine and Ten are Skylla, the many-headed monster, and Charybdis, the dangerous whirlpool.

11) At the Isle of Helios, the sun god, Odysseus’s men refuse to obey his orders and slaughter the sacred cattle, and they all end up dying.

12) Finally, Calypso is the beautiful goddess with whom Odysseus stays for seven years before getting back to Ithaca.

Let’s start with Circe. Are there connections that you see Morrison making to Homer’s Odyssey, beyond just the repetition of the name?

Participant: Circe certainly gives Milkman guidance about how to continue on his journey.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: He definitely needs her advice along the way. Is Circe perceived as a kind of a witch?

Participant: The way she looks. When her appearance is described, she is old and wrinkled. She’s lived far longer than anybody thinks possible. And doesn’t she have the dogs all around her? I think in The Odyssey, Circe had pigs all around her—all those men she had changed into pigs.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Yes. On page 240, "He looked down and there, surrounding him, was a pack of golden-eyed dogs, each of which had the intelligent child's eyes he'd seen from the window." They look almost human—perhaps a twist on the men who'd been turned into pigs. Morrison’s Circe’s age is also very striking to the reader next to the fact that Milkman is really turned on by her. There's the description of her grabbing him. There's the toothless mouth gaping and gabbling at him. Then he has an erection—that sexualized connection suggests something supernatural about her allure. Her voice sounds very young. There's also that strange ginger smell that's wafting around the house.

What other connections are there to The Odyssey?

Participant: In the end of The Odyssey, when Odysseus comes back, he has to prove himself to Penelope. I think that in the end of Song of Solomon Milkman has to prove to Guitar that he's innocent. He never does convince him, but he tries to prove it. It reminded me of how Odysseus had to prove himself to Penelope before she would let him back in her bed. Milkman had to prove himself to Guitar.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: I would agree about proving himself to Guitar, but the Guitar who's trying to kill him might be more closely connected to the suitors in terms of people of a former community who try to then take your life. These are the people who are supposed to be loyal. Who is Morrison’s Penelope, the wife who has remained loyal at home?

Participant: Hagar.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: OK—What might Morrison be saying about women's loyalty, women who are required to stay home and be loyal and faithful? In the novel, we have characters who fly away and can escape, and those who stay closely wedded to the home. For Hagar, that loyalty or faithfulness to Milkman means that if she can't have him and he won't have her, she's going to kill him or she's going to end up dead. Morrison makes the line between resolute faithfulness and obsessive love quite murky. So we have one possible reading of Hagar as a Penelope figure who is left home. Can you see who Calypso might be?

Participant: I think it is Sweet. She’s like a goddess who gives him everything he wants. But maybe Hagar is Calypso…. Milkman feels trapped by her, and Odysseus feels trapped on Calypso’s island. It could work in different ways.

Participant: It seems to me where his home is and where his people are isn't where the Deads are. Where his people are, like in Odysseus's Ithaca, Odysseus has to get back to the same physical place. For Milkman the journey is not about returning to the same geographical location, but to a real sense of home and his people. In Song of Solomon it means something other than geography.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Definitely. Morrison might be alluding to this ancient Greek story and tradition but saying that this does not work as an exact parallel because our cultural experience is different. She's twisting and tweaking it in particular ways. What does home mean? Is home a place?

Home for Odysseus is where his wife and child are, but it's also where he has the most power. He's a king. He's got all of his money. He has a huge castle and all of these material belongings. Poor Milkman, as he's going through his journey, has to get rid of all of those material trappings to become his true self. It's not going to them but rather getting rid of them. There's that great scene where he's walking to the cave and his expensive Florsheim shoes get all wet and muddy. His gold watch gets shattered. All of his physical possessions have to drop away.

Participant: The Sirens could be Ryna’s Gulch; there’s that ghostly song that's very alluring, but the gulch is rocky, a dangerous place.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Good! Any others? What about Hades, the dark place of the dead?

Participant: The Land of the Dead. Maybe it’s the cemetery where Ruth goes to visit her father?

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Interesting! How about when Milkman is on his journey? The hunt, in the woods, is one possibility. It is dark, and Milkman passes over into the realm of the dead when Guitar tries to kill him. Also, he makes connections to the past and history, like Homer’s Odysseus makes connections to people from his past as he speaks with their ghosts.

There’s also the cave. It’s where the dead body is when Macon sees the ghost of his father.

Also, you might look at the hunt in terms of a revision of what happens, the slaughter, on the Isle of Helios. There's the slaughter of the cattle, which is definitely a taboo. In Song of Solomon there is the slaughter of the cat, but it's in a sacred and ritualized performance.

Participant: This ritual. That was fascinating to me.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: What did you do with it?

Participant: They offered him [Milkman] the heart of the bobcat, and he takes that. At the same time, he's remembering Guitar's words about “Everybody wants a black man’s life” (281) and “It is about love. What else? …. What else? What else?” (282). To me, it was almost like a religious ritual or rite: he's becoming who he's supposed to become through this slaughter.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: It's a part of what he's gone through before, a past experience, memory, other people, and influences.

Participant: He's making sense of it through this ritual.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: This is partly why we cannot read Morrison only through The Odyssey and through Greek myths. It can't work because that's exclusively a European tradition. Morrison’s novel can't fit neatly, one-to-one, with Homer’s epic poem. In the next part of our discussion we will look at references that provide yet another layer that is essential to the understanding of the novel. We can't just look to one particular set of traditions or beliefs.

Participant: On p. 283, at the end of the bobcat scene, "Milkman looked at the bobcat's head. The tongue lay in its mouth as harmless as a sandwich. Only the eyes held the menace of the night." There's something going on here, and I don't know what it is. Why the tongue versus the eyes?

Participant: Where it says the peacock is soaring away, riding on the hood of the Buick, it made me think of First Corinthians, when she went on top of the hood of Porter’s car. I wondered if that was symbolic there too.

Participant: I think that's one of those places where you try to make a connection, but it just doesn't work.

Participant: Maybe that's it.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Some people wonder why the peacock in there is white. Peacocks aren't usually white. Do you remember when the peacock appears?

Participant: Doesn't the peacock appear the first time before Milkman starts on the journey?

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Yes—think back to The Bluest Eye.

Participant: When they steal the gold—really the bones—is when they first see it. Then they go off on a hunt for the peacock, and they can't catch it. (178).

Participant: It can't really fly because it's weighed down by its jewelry.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: What might that mean?

Participant: So this is a coming of age ritual, and the biblical thing?

Participant: Milkman has to get rid of all of his material possessions.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: All that jewelry weighs the peacock down. Note that it's specifically a white peacock that they're chasing after, and all the jewelry weighs it down. It can't fly. It can't escape. All of that obsession with material things is too burdensome. We can talk about this, too, in terms of Macon and his keys and his obsession with ownership. He has completely contorted his father’s dream of achieving the American Dream of property, prosperity despite one’s humble beginnings. This idea of ownership of property would have been incredibly powerful for those who had once been considered property themselves. Recall the old men in Danville who remember the meaning of Macon Dead’s farm. It said to them: “We live here. On this planet, in this nation. . . . we got a home in this rock, don’t you see!” That would seem to be an allusion to the Pilgrims landing on Plymouth Rock and the founding of the nation. The farm urges them: “Nobody starving in my home; nobody crying in my home, and if I got a home you got one too! . . . . Grab this land! Take it, hold it, my brothers . . . shake it, squeeze it, turn it, twist it, beat it, kick it, kiss it, whip it, stomp it, dig it, plow it, seed it, reap it, rent it, buy it, sell it, own it, build it, multiply it, and pass it on—can you hear me? Pass it on!” (235).

Participant: So Milkman’s and Guitar’s chasing the peacock is a false quest for the gold.

Participant: It has also to do with whiteness. You think about the white bull and Freddie earlier. Anything that has to do with whiteness and whiteness as the ultimate goal, the ideal, is damaging to people.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Yes—think back to The Bluest Eye.

Participant: Toni Morrison wrote in "Romance in the Shadow” about the African presence in white America.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: That idea’s part of "Unspeakable Things Unspoken," too.

Participant: You get glimpses of this blackness in a nineteenth-century white novel.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: When you're talking about Guitar, it makes me think, too, about the lotus eaters. In The Odyssey the consumption of the flower makes the men forget. Their bodies forget after the consumption of this particular material. In Song of Solomon, Morrison inverts this idea: Guitar cannot consume sugar because his body will not let him forget. When he walks past the bakery or hears people talk about candy, he throws up. Recall the divinity that the white man brings for the children when Guitar’s father is killed in the accident at work; the man also pays his mother $40 in compensation for the death of her husband. So how much is a black man's life worth? $40! She smiles and accepts it and uses part of the money to buy peppermint candy. The scene with the bone white and blood red candy is mentioned again and again. Guitar is disgusted with her acceptance of the situation, her lack of anger, bitterness, or resentment, and this gets transferred to disgust for sweets.

Many African American writers talk about sugar. This subject connects Morrison’s work to writing from a larger African diaspora community—not just US Africans, also Africans in the Caribbean. All of those African communities were exploited in sugarcane production during slavery and afterward. In Paule Marshall's Praisesong for the Widow (Dutton, 1984) for example, the title character keeps eating ice creams and candies. When she's making her journey from the island of Grenada to that of Carriacou to attend a traditional African ceremony, she throws up everything. She can't keep this sugar in her body, because it speaks to the history and the oppression of her people.

One more Odyssey allusion that I'd like to point to is the Cyclops (267). Although this is an allusion to the Greek myth and this European tradition, Morrison is again bringing African American history and culture into play, so the reference becomes much more complex. Note the scene in Solomon's General Store where Milkman’s just insulted all of these men when he says, "Just tell me if the car is broken. I'll just buy another one." These men have no money, and he's feeling his crotch as he's watching their women. As all of these things happen, they start a battle of words.

This is a reference to the dozens. In the African American tradition the dozens is a battle of words and wit. Going back and forth, you trade insults, and lose the game if you lose your temper, or if you strike out physically. It should all be about the mind, the intellect, and the words. Milkman only slowly becomes aware of his situation: “Milkman made his voice pleasant but he knew something was developing.” The conversation seems normal, but then the topic starts veering away from social norms:

"Pussy the same everywhere. Smell like the ocean; taste like the sea.” . . . .

“Maybe the pricks is different [up North].” The first man spoke again.

“Reckon?” asked the second man.

“So I hear tell,” said the first man. . . . “wee, wee little."

That is a direct insult to Milkman's masculinity. He takes up the challenge:

"I wouldn't know. . . . I never spent much time smacking my lips over another man's dick.” Everybody smiled, including Milkman. It was about to begin. (emphasis added)

“What about his ass hole? Ever smack your lips over that?"

We see that it's getting really intense. Then they talk about the Coke bottle. More ugly words follow, then the knife glitters in the hand of Milkman’s opponent. Milkman taunts, "Where I come from boys play with knives—if they scared they gonna lose, that is" (268). The verbal battle then turns into this physical assault. When Sol is cut over his eye, and the blood blinds him, this injury to the eye, coupled with Milkman’s wit, might be a subtle reference to the Cyclops. But the scene is very much embedded and grounded in African American culture.

The Flying Africans

That takes me to the flying African myths that are on electronic reserve. The first one I’ll address is "Gang Gang Sara." This comes from a collection called Folklore and Legends of Trinidad and Tobago. An African witch, Sara, was blown from her home in Africa across the sea to Tobago, where she became a housekeeper. In her old age, she desires to return to Africa, but can no longer fly. Again, it's not a story specifically from the US, but we see how the central image of flight repeats throughout lots of different African diasporic communities, likely transferred during the slave trade.

Another of our e-readings for this lesson, "All God's Children Have Wings,” says,

Once all Africans could fly like birds; but owing to their many transgressions, their wings were taken away. There remained, here and there, in the sea islands and out-of-the-way places in the low country, some who had been overlooked, and had retained the power of flight, though they looked like other men.

There was a cruel master on one of the sea islands who worked his people till they died. When they died he bought others to take their places. These also he killed with overwork in the burning summer sun, through middle hours of the day, although this was against the law (62).

Then there's the description of this man with a forked beard (63). In the Western tradition, that might signify evil, someone devilish. But here it is something positive. This is the old man who "The driver could not understand what they said; their talk was strange to him." The man urges restraint to the enslaved woman who keeps falling down and asking, "Is it time yet, daddy?” Then finally he answers, “Yes, daughter, the time has come. Go; and peace be with you. And stretched out his arm toward her . . . so. With that she leaped straight up into the air and was gone like a bird, flying over field and wood.”

The film Daughters of the Dust (1992), directed by Julie Dash, and set in the South Carolina Sea Islands, also deals with the notion of magical escape from the horrific conditions of slavery. The recently arrived Africans, members of the Igbo nation, walk back over the water to Africa. Paule Marshall’s novel Praisesong for the Widow (New York: Plume, 1983) similarly employs this myth. For more information, see the New Georgia Encyclopedia entry on Ebos Landing.

Some people read those stories as symbolic in the way that flight, or walking back over the water, represents escape. In other words, flying away just signifies running away. Other people read the flight as a metaphor for death. According to this interpretation, death, and especially suicide, is a viable means of escape. Rather than suffer the indignities and pain and torture of slavery, some people would kill themselves. The Igbo were one of the groups of people who were not likely to be captured by slavers in Africa, because they had the reputation of killing themselves rather than be taken into captivity. Killing themselves on the ships and once they arrived in the Americas resulted in profit loss. So they weren't taken. They refused to bow down.

These stories help us to comprehend the ending of Song of Solomon, which I think is the most problematic part of the text for people—especially for Western readers who want to read narratives in terms of the real. What really happened? Does Milkman really fly? Does he commit suicide?

“You want my life?” Milkman was not shouting now. “You need it? Here.” Without wiping away the tears, taking a deep breath, or even bending his knees—he leaped. As fleet and bright as a lodestar he wheeled towards Guitar and it did not matter which one of them would give up his ghost in the killing arms of his brother. For now he knew what Shalimar knew: if you surrendered to the air, you could ride it (337).

What is Morrison doing at the end? Do you think he committed suicide? According to some perspectives, suicide is a cowardly death.

Participant: I don't necessarily agree that it was a cowardly death, because Guitar was shooting at him, and he was going to die anyway. That gave him a little control over his death.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: We have the notion of jumping, leaping towards death as a way to maintain control over his life. He is an active agent and his own pilot versus having Guitar control when he dies. What other possibilities are there for this ending?

Participant: It sounds like he's giving his life to Guitar.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: In what way? In terms of the language?

Participant: He says, "You want my life?" And he's not shouting. He’s not angry. He’s crying—he’s compassionate. "You need it? Here." It's like he's sacrificing himself in a way to whatever Guitar wanted to do to him.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: What might the implications of that be?

Participant: Instead of Guitar taking his life, it's been given. It's almost like a religious sacrifice.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Coming together rather than ending up in antagonism. Accentuating the bond rather than the fight and the tension. The end to their relationship as hunter and hunted, predator and prey.

Participant: You can connect that to the bobcat too. Love the bobcat, kill the bobcat.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Death as an act of love rather than an act of hate. The ending of the violence instead of continuing it. The laying down of arms.

Participant: Guitar is no longer bent low. He stands up.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: That's something Milkman can see even though he's on the other side.

Participant: Guitar calls Milkman his main man.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: This speaks to their relationship and the bond that they have. But consider this: even if he's leaping out in embrace of Guitar—even if the act is something that's positive, there's someone still left behind. There's always someone left behind. That's a huge part of it. The contradiction between the empowerment of flight and the abandonment involved in flying away. After Milkman finally figures out what the folk song refers to, he goes swimming with Sweet (328). He's hooting and hollering:

“He could fly! You hear me? My great-granddaddy could fly! Goddamn!” He whipped the water with his fists, then jumped straight up as though he too could take off, and landed on his back and sank down, his mouth and eyes full of water. Up again. Still pounding, leaping, diving. “The son of a bitch could fly! You hear me, Sweet? That motherfucker could fly! Could fly! He didn't need no airplane. Didn't need no fucking tee double you ay. He could fly his own self!”

Here is the independence and agency that Milkman has been seeking through the novel. He yearns for flight as a young kid. He gets demoralized when he figures out he needs wings to fly, and he identifies with Robert Smith. Riding in the Packard, when he is looking backward over the seats, he says it makes him nervous because it feels like he is flying blind. Remember the peacock that can't fly. He sees Pilate, Hagar, and Reba as ravens. There's the reference to flight when he's at their home. He describes them as ravens, because they're so eager to listen to everything that he has to say, in contrast to his own family who seem very dead and depressed. Those three women fly outside the bounds of society. They are free in lots of ways. Other people can't be free, because they're so contained by social norms.

After this celebration of his discovery, he comes to understand the people left behind. When he goes back to tell Pilate what he's found out (332), he comes to that awareness. "What difference did it make? He had hurt her [Hagar], left her, and now she was dead—he was certain of it. He had left her.”

His flight away from Hagar leaves her totally devastated.

While he dreamt of flying, Hagar was dying. Sweet's silvery voice came back to him: “Who'd he [Solomon] leave behind?” He left Ryna behind and twenty children. Twenty-one, since he dropped the one he tried to take with him. And Ryna had thrown herself all over the ground, lost her mind, and was still crying in a ditch. Who looked after those twenty children? Jesus Christ, he left twenty-one children! Guitar and the Days chose never to have children (332).

He feels for the people who are left emotionally suffering and psychologically damaged when the individual makes the decision to fly.

Participant: Milkman's life starts with man's quest for the secret of flying on p. 1, when Mr. Smith is leaping from the hospital roof. We wonder at the end whether he’s finally found that answer. The last sentence is, "If you leap into the air you can ride it."

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Can you elaborate on that a little more?

Participant: Robert Smith obviously doesn't have the secret to flight, because when he jumps from the roof, he dies on the day of Milkman's birth. He tries to artificially make wings, and he doesn't succeed. Whether he lives or dies, Milkman has found the secret of flight.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: One of the things we might question is whether Milkman lives or dies. Morrison leaves open the possibility that he does succeed. We don’t know whether he hits the ground and dies. We definitely know that for Robert Smith. Robert Smith is tied to Porter, the guy who's up on the attic and is peeing over everyone. Again, there's that repeated phrase: "I love you all." Love is tied in there. The novel’s ending is ambiguous, and we do have lots of references to magic and magical realism, or marvelous realism. Magic is validated through the novel—for example, the ghost that people see. Remember the scene when Milkman describes a dream to Guitar. Then he says it really wasn't a dream, but he had to tell him it was a dream because he can't let him think he really saw this.

In terms of literary theory, magical realism accounts for a way of seeing the world and how it operates aside from the logic and conventions of Western belief systems.

Participant: It's not physical but spiritual.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Yes.

Participant: I'm wondering about the phrase "gives up his ghost." Usually if someone gives up a ghost, it's dying. There might be another way to read that: as giving up somebody you need to give up.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: What do you mean?

Participant: If you think of a ghost as something that's haunting you, then you need to move away from it. Perhaps Morrison allows for the possibility that giving up his ghost doesn't necessarily mean dying but rather means moving on and no longer being haunted.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Good! This might be connected to a spiritual flight instead of a physical one. One that takes you beyond where you're able to go with your physical body. Milkman achieves transcendence.

Participant: For Morrison, giving up the ghost is too much of a cliché for her to use it accidentally. I think she is asking us to think what it means to give up the ghost.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: Give up the things that haunt you, or perhaps give up the body and let the spirit fly free, or let the spirit remain where the body goes on? This is the tension that always exists in Morrison's works. As she says, it's a bumpy ride and a complicated message. What do you do with it?

Participant: Nobody can deny that it's spiritual—whether he lives or dies, but it's still transcendent. He's now a mature and spiritually complete self despite all the other problems that we know about.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: He's accomplished what he needs to accomplish.

Participant: He's ready to enter his new life, whatever that life may be. He might be back in Africa, or he might be dead and in heaven.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: We have different interpretations of where home is.

Participant: He's completed the hero journey. They say a hero leaves home reluctantly on a quest to come back home. It's not really the same place he started, but his is a home where he's becoming himself, whoever that is.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: This idea of—hmm… I don't want to say spiritual home because that might suggest something exterior—a home in oneself, in a particular way.

Participant: What about reading it as a journey back toward Africa? Is that a way that people read this book? Could it be read that way?

Dr. Giselle Anatol: I think that's complicated by the presence of Heddy and Sing and that whole line of the family tree. The “back to Africa” movement is problematic because African American people have grown up in the United States. Theirs is a specifically American experience, that would be foreign in Africa, even though there's African influence present.

Participant: In Eugene O’Neill’s play The Emperor Jones, the main character is working his way through memories. They stop being his own memories and become a collective memory of his family and his friends and moving backward in time. He ends up in Africa. It's a collective consciousness that he comes into.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: I think it makes an interesting comparison, especially for the ways the people of different eras would perceive what Africa meant. Remembering Marcus Garvey in the 1930s and his back-to-Africa movement, thinkers much later in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s were still struggling with the issue of whether it is feasible to think of Africa as home or as a safe space or a spiritual center. It's shifted over the years.

Participant: I think Milkman is dead. You may all disagree with this, but it all goes back to what we started with, with the names. He fulfills himself. He becomes the person he's always wanted to be. It's the end of his life. He's dead. It just works for me.

Participant: You find yourself; you lose yourself. It has the biblical leanings. He lays down his life for his friend, his brother. He's a sacrificial hero. Then it's Guitar who would have a rebirth of life.

Participant: Morrison won’t tell us what it means, because she's leaving it up to the reader. Readers bring all their own experiences to the book. If you're a pessimist or an optimist or whatever, you're going to believe a certain way. I agree with you. I think he died.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: I would argue with you—partly because that's my job as the course instructor! I say that he's alive—that he has accomplished flight. She does leave it ambiguous.

Participant: Can you talk more about the implications of actual flight?

Dr. Giselle Anatol: It defies notions of logic and the reality that has been constructed by Western ideas, especially in the fields of science and history—those fields linked to an alleged objective truth. Newspapers, fact, objective truth, law—think about the idea that everyone is equal under the law. There are all of these ideas that are supposed to be indisputable. We can't fly, because we have gravity. Morrison undercuts so many of those facts in her narrative. We are not all equal under the law. Newspapers are not unbiased. This becomes clear in the novel when the folks in the barbershop look for the news story of Emmett Till’s murder. They joke about the section and page the article will be on. This discussion highlights the arbitrariness of the reporting. When Guitar tells Reba that he'd never heard that a black person won the Sears Roebuck contest—he never saw it in the newspaper—Morrison is commenting on all of those ways that history and “facts” are constructed according to who's in power. If the author is undercutting certain ideas that are ostensibly incontrovertible, we must also consider that she’s undercutting or subverting the notion that people can't fly, although we’ve been taught that it's impossible physically.

Participant: I would go with the spiritual flight. The physical flight is a little hard for me to prove.

Fact or Fiction?

Dr. Giselle Anatol: When people teach Beloved, they do different exercises. I heard of a project involving two high schools. In one English class it was the students’ job while reading the book to prove that Beloved was a real person. She was an escaped slave who maybe had some kind of trauma, loss of memory, and there are lots of clues throughout the text that allow you to believe that. The other school was supposed to prove that Beloved was actually a ghost. The two classes had a conversation at the end of the project. For people who want to believe that Beloved is real, there is textual evidence that fits conventional logic and the rules of everyday society that we're expected to believe in. We're not supposed to believe in ghosts or be superstitious. If we believe in ghosts, we're considered foolish, or unenlightened. Morrison allows us to see that that is a possible reality—and definitely a reality for the people in the book, if not feasible for people outside this context.

Participant: Talking about how people want this narrative to be logical and factual, remember Pilate’s sense of history about what happened when asked in what year her daddy was blown into the air. She says it was the year the Irish were gunned down. Of course, the first thing I did was go to the history books to check which year the Irish were gunned down. Is there a historical reference for that or is it just one of those things that never makes newspapers that a person carries in memory, and so Morrison is suggesting that memory is another type of history.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: It makes me think of the historical research on how the Irish “became” white. The Irish were not perceived as a white racial group when they first immigrated to the United States. They suffered a lot of discrimination, and our contemporary lack of information about the year they were “gunned down” might reveal another site of erasure of a particular group of people in American history. I think one could use this book in a discussion of history as well as in an English class. You can talk about the ways that Morrison is presenting history and the ways that she is questioning the history that we learned. She gives us lots of dates. There's 1918, when “colored” men were being drafted. 1953 until 1955 were the Montgomery bus boycotts. She talks about the 1963 Birmingham church bombing. Those events are given specific dates, but she also mentions Malcolm X, the Irish people being gunned down, the lynchings, the Air Force pilots who were part of the 332nd fighter group, Truman, FDR, TB sanitariums, migration, Kennedy and Elijah Muhammed, African American and Native American race relations and interwoven historical narratives.

Participant: Everyone wants to have an answer that he's dead or not dead. I read it and thought for a couple of minutes. I think Morrison believes that it doesn't matter or she would have spelled it out more clearly. The main thing is that Milkman reaches his quest. He's found what he needs to be, and he's home now. Whether he physically lives or dies, it doesn't impact the big picture of what life is about.

Dr. Giselle Anatol: She doesn't want it to be pinned down.

Participant: Which is the better answer? Some will say he didn't have a life. If he had lived, he'd always worry about Guitar, so he's better off dead. That's the answer that I can count on.